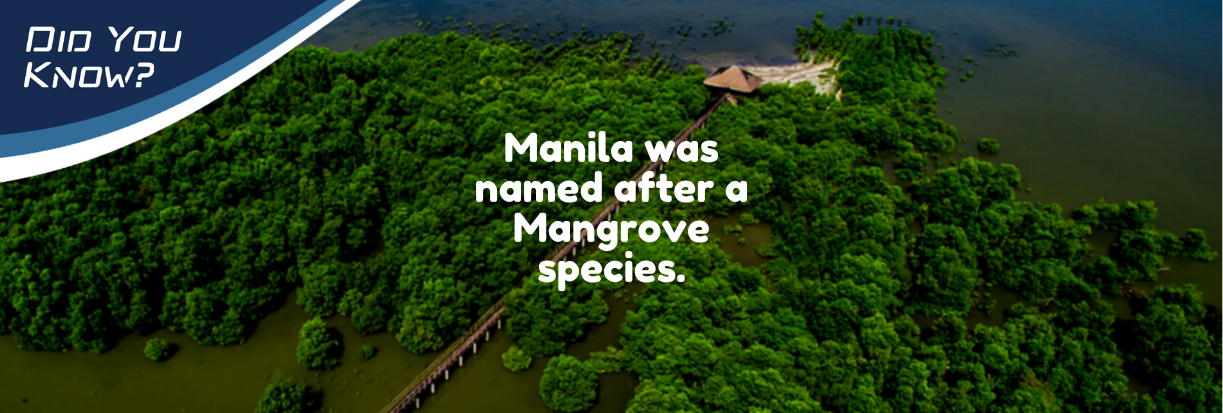

The word “Manila” originated from the phrase “may nilad” or “there is nilad” with nilad referring to the mangrove species of Scyphiphora hydrophylacea. This species was once abundant along the coast of Manila Bay and Pasig River. Other species of mangroves that can be found in Manila Bay are the Saging-Saging (Aegiceras corniculatum), Api-Api (Avicennia marina), Bungalon (Avicennia officinalis), Nipa Palm (Nypa fruticans), Bakauan Babae (Rhizophora mucronata), and Pagatpat (Sonneratia alba). Mangroves are one of the major habitats in Manila Bay. These are a group of shrubs and trees that thrive in coastal intertidal zones which are areas that submerge during high tide and above water during low tide. Mangroves grow in areas with low-oxygen soil and only survive in tropical and subtropical regions. They survive at temperatures above 19° C, not tolerating fluctuations exceeding 10° C. (http://bit.ly/HabitatConditions). They can be recognized by their dense tangled roots which also allow them to stand the daily rise and fall of tides.

Mangroves provide several ecosystem services in the coastal environment. Mangrove forests provide nesting grounds, growth areas, and shelter for some fish and crustaceans. Since the Philippines is vulnerable to typhoons that can bring about strong winds and storm surges, mangroves help in coastline protection and prevention of erosion of coastal sediments by reducing the force and height of waves that reach the shores. Moreover, they serve as a good carbon sink wherein carbon deposits are absorbed in the mass of the plant and in the soils in mangrove ecosystems. Over 200,000 hectares of mangroves in the Philippines can sequester the amount of carbon that is equivalent to emissions of 3 million cars. The carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere through the coastal ocean ecosystem is referred to as blue carbon. http://bit.ly/ForestCarbonFactsheet

What is Blue Carbon? Check out The Blue Carbon Initiative at thebluecarboninitiative.org

Unfortunately, it was found that the area covered by mangroves in Manila Bay and nearshore areas decreased by about 50% from 1996 to 2016. This is based on the data acquired from the Global Mangrove Watch (https://www.globalmangrovewatch.org), an initiative which uses remote sensing for the monitoring of mangroves worldwide. In 1996, around 497 ha of mangroves can be seen along the coast of Manila Bay. Twelve years later, this area decreased to around 267 ha, which is almost half the prior estimate. In 2010, it decreased further to about 230 ha, until a slight increase was recorded in 2016 (area resulting to 251 ha). This is coherent with the study that noted a 10% decrease in the nationwide mangrove cover between 1990 and 2010 (Long et al., 2013). In general, the decline may be caused by overexploitation of coastal communities, conversion to agriculture and fish ponds, and settlements.

In recent years, various mangrove rehabilitation programs have already commenced to counter the degradation of mangrove cover in Manila Bay. In Bataan, there is a Bataan Integrated Coastal Management Program which aids in mangrove monitoring and promotes mangrove tree planting as part of their ecotourism. In Bulacan, the Mangrove Rehabilitation and Management Project commenced in 2017 to restore the mangroves in Malolos. The Nilad for Maynila is an effort to bring back the “nilads” in the city’s coast. The Las Piñas–Parañaque Critical Habitat and Ecotourism Area (LPPCHEA) remains to be a protected area which houses mangroves among other wetlands. Recently, the Battle for Manila Bay was launched last Jan. 27, 2019, involving all the provinces surrounding Manila Bay to restore coastal mangrove forests in the area. Sources: Garcia et al. (2013). Philippines’ Mangrove Ecosystem: Status, Threats, and Conservation. Retrieved from (http://bit.ly/MangroveDecline). Note: GMW datasets from (https://www.globalmangrovewatch.org) were digitally processed to provide area estimates of mangrove cover.

In a study of eight mangrove rehabilitation projects in the Philippines, it is found out that despite sufficient funding to rehabilitate thousands of hectares of mangroves over two decades, the long-term survival rates of mangroves are generally low at 10–20%. Two of the main reasons include planting inappropriate mangrove species and choosing inappropriate sites. For instance, in sandy substrates of exposed coastlines, the favored but unsuitable Rhizophora (bakawan) are planted instead of the natural colonizers Avicennia and Sonneratia. Mangroves thrive in places where freshwater mixes with seawater on muddy soil. However, many of the ideal sites have been converted to brackish water fishponds, so mangroves are inappropriately planted on seagrass beds and tidal flats where they don’t naturally grow. It is important to understand changes in hydrology and fresh water supply, and loss of sediments, among other ecological and social conditions that help in mangrove restoration. This can be achieved by strengthening the information, education, and communication programs, and involving local communities in the protection, conservation, and management of mangrove areas. (http://bit.ly/PH_Mangrove)

Room 235, National Hydraulic Research Center,

Room 235, National Hydraulic Research Center, esmart.im4manilabay@gmail.com

esmart.im4manilabay@gmail.com

No responses yet